North Korea's seizure of the USS Pueblo nearly engulfed the Korean Peninsula in yet another war.

Essay

The USS Pueblo Incident

By Mitchell Lerner

Introduction

Objectives and Mission of the USS Pueblo

Her propulsion system consisted of two eight-cylinder diesel engines with twin screws, which could reach a top speed of thirteen knots, about one-third of a conventional American destroyer. The ship’s steering engine failed regularly, often leaving the ship floundering in the ocean until tugboats could arrive for a rescue. Both internal and external communication systems were extremely erratic, and at times of crisis were all but useless. The LORAN navigation system was inaccurate, sometimes off by up to five miles, and the compass' directional errors sometimes exceeded 20 percent. The ship was armed with only a handful of small arms and two .50 caliber machine guns, which, because of their light weight, their propensity for jamming in conditions of extreme cold and saltwater, the crew’s unfamiliarity with their operations, and the lack of protection offered to anyone trying to operate them, were of little use under the specific conditions in which the ship would be operating.

Despite the fact that Pueblo carried the latest in American signals intelligence technology, the ship had no self-destruct system, and its facilities for the destruction of classified information, consisting primarily of twenty-two weighted sacks that could be filled with papers and thrown overboard and a few very slow paper shredding machines, were inadequate for a ship that carried hundreds of pounds of top-secret documents. So problematic was the ship’s condition that in August 1967, just five months before the ship’s first mission, the Board of Inspection and Survey conducted three days of continuous testing, and found 462 separate deficiencies, 77 of which were so severe that inspectors ordered that they "must be corrected" before the ship began a mission. "Material deficiencies," they concluded, "exist in the ship that substantially reduce her fitness for naval service” (Quoted in Trevor Armbrister, A Matter of Accountability, p. 148-49).

Despite the fact that many of these problems still existed, Pueblo departed Japan as ordered on January 11, 1968. The ship’s specific orders required her to, "Determine [the] nature and extent of naval activity [in the] vicinity of North Korean ports of Chongjin, Songjin, Mayang Do, and Wonsan . . . sample electronic environment of [the] East Coast [of] North Korea, with emphasis on intercept/fixing of coastal radars, [and] intercept and conduct surveillance of Soviet Naval Units operating [in] Tsushima Straits in effort to determine purpose of Soviet presence" (Operational orders reprinted in Hearings before the Special Subcommittee on the U.S.S. Pueblo of the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives, p. 639-640).

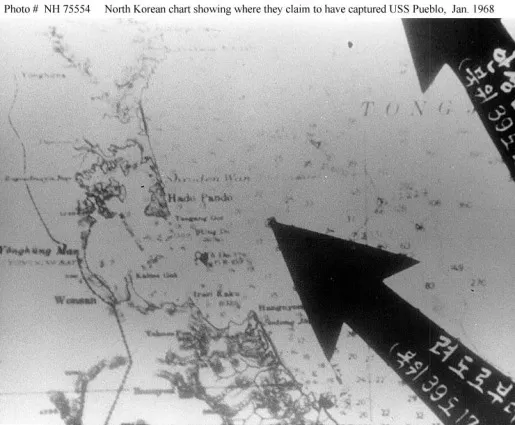

As was standard for these missions, the ship was ordered to stay at least thirteen miles from North Korea at all times, and at least 200 yards from any Soviet naval vessels encountered at sea. The first portion of the trip passed without any serious problems. Pueblo successfully navigated through the East Sea and reached Chong-jin on January 16, and then slowly headed south towards Wonsan Harbor.

For the next week, the ship intercepted various DPRK communications, although the translators’ poor language skills made it almost impossible to determine their value. On the morning of January 22, however, the situation became more problematic. While operating just outside Wonsan Harbor, Pueblo was approached by two DPRK ships, Soviet-built Lentra class trawlers converted for military use, which circled the American ship at a distance of less than 25 yards, clearly trying to determine the nature of their find. Suddenly, they turned and fled into Wonsan.

Still, the ship’s captain, Lloyd “Pete” Bucher, decided to stay in the area, confident that since his ship had been in international waters at the time of the encounter, and had been displaying no visual identification of their nationality, there was no significant danger.

The Seizure of the USS Pueblo

Bucher maintained his position until the lead ship suddenly demanded, "Heave to or I will open fire." Bucher, expecting the somewhat routine harassment that previous Clickbeetle missions had generated, was determined not to be scared off. "I am in international waters,” he replied. “Intend to remain in the area until tomorrow." Quickly, the DPRK ships took up positions alongside Pueblo, and opened fire. Eight 57mm cannon shells penetrated the ship, leaving the superstructure dented and leaking. The bridge was reduced to shambles, the external communication system damaged, and the corridors filled with blinding smoke and fire. Bucher ordered his ship toward open seas, but Pueblo was easily outflanked by the superior DPRK vessels, and the onslaught continued. There was no sign that American assistance was coming, nor any reason to believe that Pueblo could put up even the most rudimentary form of resistance. Accordingly, Bucher decided to surrender his ship. One man, Fireman Duane Hodges, had been killed during the assault, and three others had been seriously wounded.

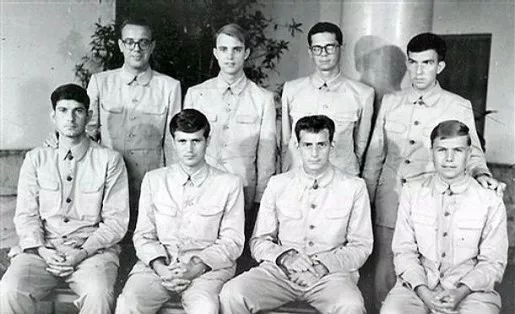

For the next few weeks the men were subjected to torture. Some were kicked and punched; some were beaten with wooden clubs and boards; some were forced to crawl on their knees or to kneel with arms elevated above their shoulders and square wooden sticks wedged behind their knees for hours; some were stripped naked and forced to sit on radiators. Beatings continued until the men signed confessions prepared for them by their captors, admitting to having violated DPRK territory for the purposes of espionage, and apologizing for having done so. Pueblo, Bucher admitted in his, had been "carrying out military espionage activities, having intruded deep into the coastal waters of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea." After fourteen paragraphs detailing these activities, the statement asked for mercy. "What I have done . . . can never be tolerated. I humbly beg of you to forgive me my crime." The rest of the crew signed similar statements, many of which were quickly fed to the national and international media, and publicized for propaganda purposes within North Korea.

The Pueblo Crew in Captivity

Much time was devoted to “re-education,” with the crew engaging in group sessions where DPRK guards lectured them on the evils of American society or the teachings of Kim Il Sung, and required them to engage in self-criticism. In March, they were relocated to a new facility, one closer to Pyongyang, that was in somewhat better condition, with rooms equipped not only with beds, tables, and chairs, but with wash pans, closets, mirrors, large tables, and two light fixtures that could be extinguished at night. Also continuing were the propaganda efforts, as the men were forced to appear in press conferences including ones broadcast by DPRK radio stations and covered by local newspapers, where they repeated their guilt and their repentance. They were also forced to write letters of admission and apology, first a public one to the Korean people, then a public one to Lyndon Johnson, and then subsequent versions to friends, family members, and public figures within the United States. Again, copies of the letters and transcripts of the public appearances were commonly used for DPRK propaganda, with a focus on both the strength and wisdom of DPRK leadership, and the need to prepare for a subsequent attack by the United States.

While the barrage of letters, media appearances, and other forms of propaganda kept the Pueblo men in the eyes of the North Koreans, the prisoners quickly faded from the attention of the American public. Unsurprisingly, the immediate response within the US was a demand for vengeance. "There should be no word mincing in our demand for the swift and safe return of both ship and crew," wrote the Buffalo Daily News, "nor should North Korea be deprived for long of the measured dose of retribution her sudden belligerency has so emphatically asked for" (Buffalo Daily News, January 24, 1968, p. 12).

Telegrams calling for action flooded the White House. One Georgia resident ordered the president to "get off your complacent rear and get the ship and its crew back," and a Florida man demanded, "Release, retaliation, or your resignation" (Telegrams from Johnson Library, WHCF, subject file, defense, ND 19/CO 151, box 205. The Georgia telegram is from Vincent Guy; the Florida telegram is from Hugh Moreland). The public outcry, however, proved to be fleeting. Quickly, the American people turned their attention to seemingly more pressing matters––Vietnam; the civil rights struggle; the presidential election; and more––and the men soon faded from the national consciousness.

The American Response to the Seizure of the USS Pueblo

The Soviets, along with most members of the Communist bloc, were clearly worried by the DPRK belligerency, and frustrated by their inability to end the standoff before it became more dangerous. Soviet unhappiness with their ally sometimes even exploded into the public arena. At the April 1968 Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party Plenum, Party General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev blasted North Korea in a lengthy speech. "The measures taken in this case by the government of the DPRK appear unusually harsh," he declared. "We insistently advised the Korean comrades…to show reserve, not to give the Americans an excuse for widening provocations, to settle the incident by political means…But the Korean comrades maintained [a] fairly extreme position and did not show any inclination towards the settlement of the incident." North Korean officials, he reported, "spoke to the intentions to bind the Soviet Union somehow, using the existence of the treaty between the USSR and the DPRK to involve us in supporting such plans of the Korean friends, about which we knew nothing." Accordingly, Brezhnev had summoned DPRK policymakers to Moscow, where he informed Defense Minister Kim Chang-bong that they considered the treaty to be defensive in nature, and that military actions in the matter were "a very difficult question" ("Excerpt from Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev's speech at the April (1968) CC CPSU Plenum).

With no immediate solution emerging, President Johnson ordered the creation of a Pueblo Advisory Group to develop an overall strategy for resolving the crisis. The Advisory Group included Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, Undersecretary of State George Ball, Attorney-General Nicholas Katzenbach, CIA Director Richard Helms, and a number of other leading officials. After a week of deliberations, the group endorsed a strategy of diplomatic patience, noting that a military response would likely have not only cost the lives of the prisoners and weaken American efforts in Vietnam, but risked sparking a larger war on the Korean Peninsula that might threaten regional stability and the American position in East Asia. LBJ concurred, and despite his decision to increase the American military presence in the area dramatically, the administration would cling to a peaceful path over the next eleven months. American military leadership initially opposed this diplomatic approach, demanding a more forceful response, but soon recognized the difficult military situation and quietly supported LBJ’s decision (See, for example, oral history of Admiral U.S. Grant Sharp, NHC, volume II, p. 582-5; Daniel Bolger, Scenes from an Unfinished War).

Without active Soviet help, however, the administration struggled to find a forum for diplomatic exchange, as efforts launched at the United Nations, the International Red Cross, the International Court of Justice, and through dozens of other nations, were constantly rebuffed by Kim Il Sung.

The South Korean Response to the Seizure of the USS Pueblo

President Park made no secret of his unhappiness with the lack of a forceful American response, and consistently demanded a joint US-ROK military response against the North, or at least for the US to allow a Southern response. The day after the seizure, in fact, he warned the US Ambassador that if the North continued its aggression, a military response was "inevitable," and suggested a joint US-South Korean assault that would first bomb DPRK air fields and then attack North Korean ships off the east coast; two days later he ordered the ROK First Army into full combat status (Telegram #8515 from American Embassy Seoul to State Department, January 24, 1968, National Archives II, 1967-69 Central Files, pol 33-6, box 2258, 1/1/68 file; New York Times, January 27, 1968, p. 9; cable from Ambassador Porter to White House, January 24, 1968, Johnson Library, Korea cables and memos, volume 5, NSF, country file: Asia and the Pacific, Korea, box 255, document # 14a). Many on the Communist side also expected war, including the Polish Ambassador to North Korea. "If the DPRK does not accede to U.S. demands to return the ship and crew," he told a fellow Ambassador, "we might probably witness an armed conflict here" ("Note on a Conversation with the Polish Ambassador, Comrade Naperei, on 26 January 1968, in the Polish Embassy," GDR Embassy to DPRK, 26 January 1968).

In order to placate Park and avoid a large and costly war, President Johnson ordered a dramatic increase in American military supplies to South Korea, and approved a series of smaller steps designed to assist the ROK economy, increase collaboration between the two nations, and enhance the prestige of President Park. Such steps generally worked, and although some minor skirmishes between the two Koreas were reported, the threat of a larger war was kept until control.

US-North Korean Negotiations over the Pueblo

On February 2, the first serious talks to resolve the crisis began, with American representative Rear Admiral John Smith and DPRK Major General Pak Chung Kuk leading the MAC discussions. For the next eleven months, the two sides offered possible solutions to the standoff, with little progress. The United States offered numerous proposals, most of which revolved around the DPRK releasing the men and the ship first, after which the US would participate in some form of investigation to determine the facts and decide if an apology was merited. North Korea rejected them all. Instead, the DPRK insisted on its own solution, one the Americans soon dubbed the “Three A’s” demand: admit the Pueblo was conducting espionage; apologize for the operation; and offer assurances that it would not happen again. Only then would the crew be released; "We will be able to consider the issue of returning the crew members,” Pak declared in one meeting, “only when your side apologizes for the fact that the US government dispatched the armed spy ship Pueblo to the territorial waters of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, conducted espionage activities, and perpetrated hostile acts, and assure that it will not commit such criminal acts again” (Telegram #4261 from American Embassy Seoul to State Department, February 15, 1968, National Archives II, 1967-69 Central Files, pol 33-6, box 2255, 2/15/68 folder).

Increasingly frustrated, the Americans continued to search for solutions but no avail. In February, a reporter asked LBJ he was confident that the United States could get the ship and crew back; "No, I am not," Johnson answered glumly (Press conference #118, February 3, 1968, Johnson Library, NSC Histories, Pueblo Crisis, 1968, box 31-33, volume 13, public statements, tabs A-C). Still, with the US unwilling to act militarily and the Communist leadership unable to force Kim to be more flexible, the MAC remained the only realistic forum to find a solution.

Months of difficult dialogue kept things at a stalemate, until a breakthrough occurred in November 1968. James Leonard, the State Department's Country Director for Korea, discussed the Pueblo standoff with his wife Eleanor one evening, and admitted he saw no solution other than providing the apology the DPRK sought, but wondered how to do it in such a way as to minimize the American humiliation. Eleanor had a suggestion: agree to sign a letter providing the “Three As” only if North Korea would allow US officials to make a statement publicly repudiating it before doing so (Oral history of James Leonard, Georgetown University, Washington D.C, p. 2-4.). American officials endorsed the idea, and on December 17, the two sides met at the MAC to discuss the Pueblo for the twenty-sixth time. This time, the new American negotiator, Major General Gilbert Woodward, put forward Eleanor’s proposal, offering to sign a letter produced by the DPRK containing the “Three A’s,” but only after making “a formal statement just before signing to clarify those three points” (Telegram #288931 to American Embassies in London, Paris, and Saigon from State Department, December 18, 1968, National Archives II, 1967-69 Central Files, Pol 33-6, box 2260).

The North Koreans quickly accepted, a decision that stunned many within the Johnson administration. "It is as though a kidnapper kidnaps your child and asks for fifty thousand dollars ransom,” explained Secretary of State Rusk. “You give him a check for fifty thousand dollars and you tell him at the time that you've stopped payment on the check, and then he delivers your child to you" (Oral history of Dean Rusk, Johnson Library, transcript #3, p. 28-9). Nevertheless, the general outline of the deal had been reached.

Life Inside North Korea for the Pueblo Crew

Bringing the Pueblo Crisis to a Close

On the morning of December 23, US and DPRK officials met in Panmunjom to bring the crisis to a close. Woodward opened by reading a prepared statement. "The position of the United States government with regard to the Pueblo as consistently expressed in the negotiations at Panmunjom and in public, has been that the ship was not engaged in any illegal activity, that there is no convincing evidence that the ship at any time intruded into the territorial waters claimed by North Korea, and that we could not apologize for actions which we did not believe took place. The document which I am going to sign was prepared by the North Koreans and is at variance with the above position, but my signature will not and cannot alter the facts. I will sign the document to free the crew and only to free the crew" (New York Times, December 23, 1968, p. 3). Woodward then signed a letter written by the DPRK, in which the US, "solemnly apologizes for the grave acts of espionage committed by the US ship against the Democratic People's Republic of Korea after intruding into the territorial waters of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea." Two hours later, Pueblo crewmen poured from DPRK buses at the Northern end of the Bridge of No Return, and walked, one at a time in 30-second intervals, across the bridge and into the waiting arms of American officials.

Although the men were free from North Korea, their presence remained in the deluge of propaganda about their release that the North Koreans disseminated at home and within communist bloc circles as an example of the courage and brilliance of DPRK leadership and the perfidy and weakness of the United States. A Korean Central News Agency report boasted, "The US imperialists bent the knee again to the Korean people;" the signing, it concluded, was an "ignominious defeat of the United States imperialist aggressors and constitutes another great victory of the Korean people, who have crushed the myth of the mightiness of United States imperialism to smithereens" (Washington Star, December 23, 1968, p. 3; New York Times, December 23, 1968, p. 1). Nhan Dan, Hanoi's official paper, agreed calling the agreement "an ignominious defeat for the United States," and described the repudiation as "a base act that exposes further the obstinate and treacherous features of the United States imperialists" (New York Times, December 26, 1969, p. 6). The resolution, however, was also popular with the United States and its allies, most of which praised President Johnson’s commitment to diplomacy and dismissed the apology as an obvious sham. One exception was South Korea, where much media and public opinion derided the resolution for showing signs of weakness that would likely only encourage further DPRK provocation.

After quick medical observation in South Korea, the men were flown to San Diego, arriving to a hero’s welcome on December 24, 1968. The American military, however, quickly convened a Board of Inquiry to investigate the loss of the ship and the men’s behavior while in the DPRK. Hearings began on January 20, 1969, at the U.S. Naval Amphibious Base in Coronado, California, and lasted almost two months. A board of five admirals heard from one hundred and four witnesses, who produced over 4,300 pages of testimony. In March, the board produced a two-and-a-half pound report that recommended court-martials for two officers, including Commander Bucher, and a formal letter of admonition for the second in command. Although the rest of the crew escaped formal punishment, the court was generally critical, nothing that "with few exceptions, the performance of the men was unimpressive" (“Finding of Facts, Opinions and Recommendations of a Court of Inquiry," Naval Historical Center, Operational Archive Branch, command file, post 1 Jan. 1946, USS Pueblo, 88-94). The American public, however, greeted this decision with much unhappiness, and growing political pressure convinced the Secretary of the Navy, John Chafee, to reject the board’s recommendation. “It is my opinion," he concluded, "that they have suffered enough, and further punishment would not be justified" ("Statement of John Chafee," May 6, 1969, Carl Albert Papers, Departmental Series, box 74, folder 71).

Conclusion

With the inquiry finished, the Pueblo Incident generally faded out of the public eye. The men were quietly drummed out of the Navy, and got little help from the military as they struggled to adjust to civilian life after their ordeal. Cases of alcoholism, marital problems, and job instability would plague the crew over the course of the next few decades. Public interest in the ship flared briefly in 1985, when Congress created the Prisoner of War Medal, specifically to honor those who had suffered in enemy captivity, but the Pentagon ruled the Pueblo crew ineligible, explaining that they had merely been detained in North Korea rather than being prisoners of war, since there existed no formal conflict between the two nations at the time of the capture (New York Times, May 7, 1990, p. B-15; St. Louis Post Dispatch, June 25, 1989). Public pressure, including congressional hearings on the decision to exclude the men, convinced the Navy to relent, and the men received their medals in 1990, and then quickly faded out of public consciousness again. The ship itself remains in the DPRK as of 2013, where it found a home in the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum in Pyongyang, after years of serving for decades as a floating museum in that city’s Taedong River.