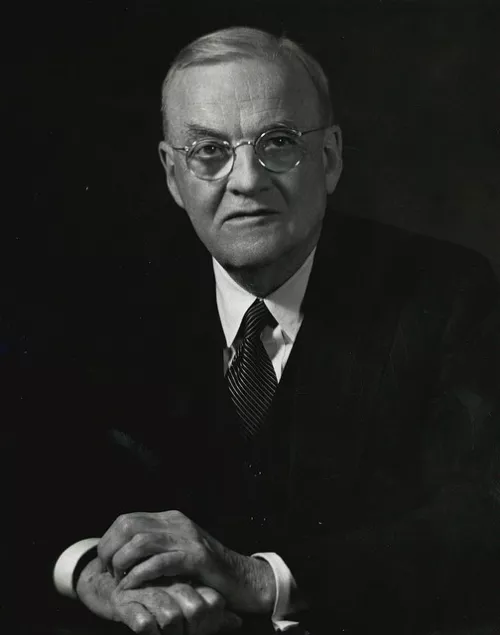

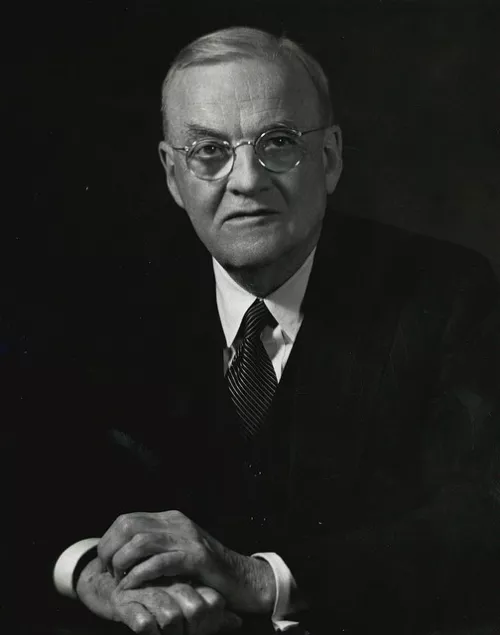

Portrait of John Foster Dulles

Photographer unknown, ca. 1953, US Government image, https://diplomacy.state.gov/people/john-foster-dulles/.

John Foster Dulles was an opponent of Truman's containment policy, and became Secretary of State under Eisenhower from 1953-1959. Dulles and Eisenhower began to speak of the "rollback" instead of the containment of communism.

John Foster Dulles was born in Washington, D.C. on February 25, 1888. As a youth, Dulles was extremely talented. He studied at Princeton, and before graduating in 1908 got his first taste of international politics when his grandfather brought him along to the Hague Peace Conference of 1907. He also studied at the Sorbonne in Paris and George Washington University Law School. He passed the bar in New York, and in 1911 he entered into law practice there and engaged in several quasi-diplomatic missions.

During World War I Dulles worked at the War Industries Board and later served at the Versailles Peace Conference. Upon his return, he became a partner in his law firm, working primarily on international cases.

In the late 1930s, Dulles’ religious feelings quickened, and he came to believe in a combination of international “institutional mechanisms” and the Christian gospel as an antidote to war and unrest. In 1940, he chaired the Commission on a Just and Durable Peace for the Federal Council of Churches. By the end of World War II, Dulles had become recognized as a leading Republican spokesman on foreign policy issues, and served on several bipartisan delegations. He served as the senior U.S. adviser to the 1945 San Francisco conference of the United Nations, and was a great supporter of international cooperation. Dulles quickly became disillusioned with the Soviet Union after World War II when he experienced Soviet intransigence firsthand at various international meetings.

In 1948, Dulles was widely touted as the next Secretary of State in the “new Dewey administration,” a forecast upset by that November’s election of President Harry S. Truman. Further disappointment followed when he lost his bid for re-election as a Senator from New York, for a seat which he had been appointed to fill in order to finish the term of the late Senator Robert E. Wagner Sr. He then returned to writing and authored War or Peace in 1950, a critical assessment of the American containment policy- then in much favor among the more sophisticated in the Washington/New York foreign policy establishment.

Truman appointed him as special representative to negotiate a treaty of peace with Japan. Dulles completed this task with skill and dispatch. He not only negotiated peace with Japan (which hardly had much say in the matter at the time), but also sorted out equitably the disposition of the lands conquered by the Japanese in World War II. He further saw to it that although the Soviet Union retained the Kuril Islands and southern Sakhalin, the U.S. continued to exercise control over the Ryukyu, Bonin, Marianas, and Caroline Islands and maintained military base rights in Japan and Okinawa.

Domestically, Dulles proved effective in convincing the Joint Chiefs of Staff of the necessity to give up control of Japan. (The JCS apparently had plans secretly to rearm the Japanese.)

Dulles enthusiastically supported Truman’s decision to intervene in the Korean War, which appeared in print a mere five days after the North Korean invasion. Typically, Dulles termed Truman’s decision as “courageous, righteous and in the national interest” in his New York Times article entitled “To Save Humanity from the Deep Abyss.” But by 1952, Dulles was characteristically denouncing Truman’s containment policy as “negative, futile, and immoral.”

Dulles was the inevitable choice by Eisenhower as Secretary of State. The two soon forged a close personal bond, although the President frequently felt constrained to moderate his Secretary’s more perfervid evulsions. They developed a "New Look" defense policy, which sought to combine fiscal solvency and a credible deterrent through heavy reliance on nuclear weapons. Although both called publicly for the “roll back” of communism, and the “liberation” of those held captive by its “despotism and godless terrorism,” Eisenhower cautioned his Secretary of State to add the phrase “by all peaceful means.” Alas, there was to be no roll back or liberation, and the new administration settled for a near-status quo antebellum truce in Korea, and later did nothing except protest the Soviet crushing of Hungary’s attempt to liberate itself from communism.

The first Eisenhower administration is generally credited with ending the Korean War by quietly letting the communists know that the administration had been seriously contemplating an extension of the war, and even the potential use of nuclear weapons. Here was an early example of the “brinksmanship” that was to prove so controversial a part of Dulles’ dealings with the Soviet Union as Secretary of State. But the death of Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin in March 1953 seems to have had much to do with weakening communist resolution to continue the struggle.

Dulles and Eisenhower in some ways proved as tough with their ROK ally as with the communists. As ROK President Syngman Rhee planned to sabotage the truce talks at Panmunjom, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, with Dulles’ compliance, drew up a contingency plan to overthrow Rhee if this were deemed necessary to keep the truce talks going.

Dulles retained the respect and affection of Eisenhower to the end of his life. He never moderated his moral anti-communism, and claimed to be perfectly willing to “go to the brink” of nuclear war to demonstrate America’s resolution against communist aggression.

John Foster Dulles died on May 24, 1959, after a long and courageous struggle with cancer, at the age of 71.